Editor’s note: This article first appeared in a 2018 issue of Kansas Alumni magazine, the precursor to Crimson & Blue. We’ve republished it online several years later for the growing audience interested in KU’s club hockey team, which is still going strong.

Yo juego hockey.

When his Spanish teacher asked students to introduce themselves to a classmate, Andy McConnell turned to an unknown guy seated nearby and said, en español, “I play hockey.”

Or, rather, he did play hockey. McConnell grew up playing youth hockey at Kansas City’s limited venues and, as with all talented junior players and their devoted families, far beyond. When he arrived at KU, McConnell immediately sought out the men’s ice hockey club team.

“It ended up being one of the reasons that I wanted to go to KU,” recalls McConnell, j’16. “A lot of my friends that I grew up playing hockey with were here and were planning on playing with the team. So I joined up.”

What he found here was not good.

“It was just rough,” McConnell says. He concedes that he didn’t help his hockey dreams by also joining a fraternity, but it turned out his frat brothers were the only true team he identified with during his first months on Mount Oread. Hockey, for the first time in his life, let him down.

“The team that was here was just kind of splintered,” he says. “We weren’t really that good. We were losing quite a bit, and a lot of the friends I originally joined up with stopped going. I finished it out until the end of the semester and told the coach I was going to stick with the fraternity and focus on my grades.

“I didn’t lose love for the sport, but it wasn’t the same experience I had had in high school that brought me so much enjoyment. I kind of hung ’em up for a while. I didn’t think I would do it again, at least not competitively like that.”

Details of the recent history of KU men’s ice hockey are, at best, muddled, especially when attempting to recreate a precise, year-by-year timeline of what happened when. What is known, though, is that the club team folded, leaving behind a trail of hurt feelings and bad debts.

There were no prospects for the sport’s return, until McConnell heard his classmate’s reply:

Yo juego hockey.

Rhett Johnston grew up playing hockey in Scottsdale, Arizona. He rose to amateur hockey’s elite AAA level, yet certainly didn’t come to KU for hockey, because hockey wasn’t here.

“When I showed up to school,” says Johnston, b’16, g’17, “there was no team. At all.”

But when “Yo juego hockey” was met with “Yo juego hockey,” an unlikely hockey renewal suddenly began. Half a decade later, the sport has been reborn.

KU has ice hockey? You’d better believe it.

The dark days behind them, today’s KU skaters take the ice in swank Jayhawk jerseys, win a whole lot more than they lose, unabashedly share their playoff dreams, relish victories over Mizzou while eagerly pointing toward their Feb. 15 Border Showdown renewal, and pine for the day when students and alumni cheer them on in numbers the team has seemingly earned.

“Not very many times in life, at least that I’ve noticed, do you get opportunities to put your hat on something that can really stick for years to come,” says McConnell, who closed out his renewed playing career two years ago and his since volunteered his time as the club’s head coach. “You have that opportunity here, and I use that as a selling point to a lot of players. We’re still a young club. There’s still so much potential for this to become something really impactful. At KU. In Lawrence. In Kansas City.

“To be honest, people just don’t know about it. Yet.”

Blame it on the “The Mighty Ducks.” The 1992 Disney movie spawned an NHL franchise in Anaheim, California, and lit boyhood fires for a sport previously unknown in the McConnell family of Liberty, Missouri. Andy and his younger brother, Preston, grew up far from hockey, but close to theatres, and he was hooked.

“I just kind of fell in love with it and really wanted to do it,” Andy recalls. “Eventually, after prodding and begging, my parents got me enrolled.”

Says Preston, now a senior forward and KU’s leading scorer, “He was persistent and would not take no for an answer. Finally my mom told my dad, ‘We’ve got to get this kid playing hockey.’ So Andy started playing, and I was the little brother who always wanted to do what he did.

“But yeah, ‘The Mighty Ducks.’ It would be funny to take a poll to see how many kids started playing because of that movie.”

Unlike other sports that can shuttle young newcomers directly into skill development, the McConnell brothers first had to clear hockey’s primary hurdle: They had to learn to skate.

“Take a football player and put some hockey skates on him and see how well he does,” says assistant coach Chase Pruitt, e’16. “It’s just a whole different sport. It’s not something that you can pick up and start playing. I wish you could because we’d have a lot more involvement.”

Outside of hockey hotbeds in northern states like Minnesota and Wisconsin, youth hockey is rarely sponsored by schools. It’s a community sport, funded by parents, and players and families routinely endure endless hours of drive time, traveling to practices at inconvenient rinks and games against distant opponents.

It seems a plausible estimation that hockey features three universal rites of passage: learn to skate, log a ton of road miles, and spend bushels of money on the first two, along with equipment that is shockingly expensive. A good set of skates, for instance, can now cost more than $1,000, and might not last a competitive player more than a year.

All of which helps explain why KU players are completely OK with paying $1,200 in dues each season and commuting to twice-weekly practices—usually starting around 10 p.m., thanks to the difficulty of booking ice time—at Line Creek Community Center, in North Kansas City, and weekend home games at Centerpoint Medical Center Community Ice, a cozy rink adjacent to Silverstein Eye Centers Arena, in Independence, Missouri.

To answer the two questions invariably raised when the subject of KU hockey arises: Yes, KU has a team, and no, the Jayhawks do not play in Lawrence.

“For sure I wish the drive was 10 minutes away. That would be perfect,” Preston McConnell says. “But, you’d probably go to practice and leave. Being forced to make that drive and have some conversation and get to know your teammates is really beneficial, and I think it’s made our team a lot better.”

When the rare grousing does surface, Preston McConnell shoots it down with college-age logic: “You’re going to be up until 1 either way; you might as well just go play. And Andy, Rhett and Chase have to wake up at 6 a.m. and go to work. You get to sleep in and you don’t have class until 3 tomorrow. What’s so bad about it?”

Winning helps. When KU hockey was losing—often by double digits—shuttling to North Kansas City and Independence was miserable, not beneficial.

After discovering their shared interest—Yo juego hockey—Andy McConnell and Rhett Johnston forged a friendship that quickly grew beyond their Spanish class. McConnell recalls that it was Johnston who was “really adamant” about restarting the KU club hockey team, efforts that he and another player, Chase Pruitt, supported.

After meeting with officials at KU Recreation Services, which supervises the sport clubs program, Johnston discovered a pile of debts for ice time purchased but not paid for at Kansas City arenas.

“We were forced to remedy everything the prior entity did wrong,” Johnston says. “So we were on probation even from the school when we started. Slowly and surely we started gaining more trust.”

The new team’s first two seasons were limited by finances, opportunity and roster depth. Bad feelings from schools that had been stood up—the dreaded “no call/no show”—by the previous KU team made scheduling its traditional opponents a near impossibility and prevented a return to the American Collegiate Hockey Association.

KU hockey was even a pariah on campus. Far from being eligible to return as an official sports club, KU hockey was also prevented from registering as a student club for a year. Once it did, the team received a mere $500 from the Student Involvement & Leadership Center.

“It was bad,” Andy McConnell says. “We were hated in the league, and were hated, kind of, by the school, which is totally understandable. So that first year, you’ve got to play so many games, you’ve got to get in good standing with everybody, you’ve got to get your players. It was like trying to ski a steep learning curve.”

With limited finances, the team could afford only an hour of practice per week, and didn’t even have a coach. “It was a jumbled mess of voices those first two years,” McConnell says.

Players had to schedule ice time—paying time-and-a-half to eliminate debt at area rinks—while also recruiting new players and scheduling opponents.

“I can remember my freshman and sophomore year, we’d lose to Arkansas and Mizzou by double-digits,” says senior forward and team captain Brent Bockman. “Now we expect to beat them every time. We know where we came from. We have a chip on our shoulder.”

Near the end of their second season, the Jayhawks found themselves wavering outside Mizzou’s home arena. Although they’d beaten Missouri once the previous year, the Tigers had also handed KU a 16-1 loss. While the KU team improved in its second season, thanks to an influx of talented young players who were slowly filtering into the club, Mizzou—an ACHA Division 2 club, compared with KU’s Division 3 status—had improved even more.

“We had played them that Friday night and we got absolutely tossed,” McConnell says. “There were injuries. We were super-short benched, with maybe 10 guys. It was the end of the season, you’re already tired, you’re beat up, you know you’re going to lose. It was one of those ‘do we want to do this?’ moments. And I remember asking exactly that.”

Huddled around their cars, the Jayhawks took a vote. Leave now, drive home, call it quits. The game, the season, the club.

Or, enter the arena, take the punishment, and keep pushing forward.

“We were really bruised up, injured, and we barely had enough guys to play a game,” says senior goaltender and club president Will Dufresne. “Eventually we decided in the parking lot that we’re here and we’re going to play. We can look back at it now and laugh, but it was a low point.”

KU hockey clawed its way back to probationary sports club status in spring 2016, and spent last season proving the team’s worthiness to the ACHA, opponents, and, most critically, KU Recreation Services.

“They had to show they were serious, because it came back on us, as well,” Dave Podschun, d’12, assistant director of sport clubs, says of the previous group’s meltdown. “That’s part of why we set those parameters for them to take steps to slowly get back. We wanted to make sure they were committed to getting the club on the right track. And they are. They really are committed to making sure they keep the club’s good name now that they’ve reestablished that.”

The 2016-’17 Jayhawks also established themselves on the ice. Buoyed both by pride in perseverance as well as an ongoing flourish of talented new skaters, KU went 15-3-1 and on Feb. 23 jubilantly celebrated a 5-2 victory over Missouri in a packed Silverstein Eye Centers Arena.

“Something clicked, and we started winning,” Bockman says. “Everybody started buying in. It was a culture change.”

Finally off probation, KU hockey this year received $9,000 from KU Recreation Services. Along with players’ annual participation fees, the team can now afford two, and sometimes three, practice sessions each week. It is scheduling better opponents, and still concluded the fall season 14-5, including 12-2 and 9-4 victories over Missouri and winning records against Creighton and Nebraska.

KU finished the semester ranked No. 8 in its ACHA division; the top 10 teams in each division advance to the playoffs.

See KU’s club hockey team in action in their December 2017 match against Washington University in St. Louis—a 5-4 victory for the ’Hawks—and hear from players about the team’s culture and camaraderie.

With only a few games remaining in the regular season—Jan. 19 and 20 at Missouri; Feb. 3 and 4 at Robert Morris University in Peoria, Illinois; home games Feb. 9 and 10 against South Dakota State; and the Feb. 15 Border Showdown against Mizzou at Silverstein Eye Centers Arena, touted as the “Rivalry at the Rink”—Dufresne cautions that not many on the team are aware that the ACHA this year switched its rankings system from a coaches’ poll to a “finicky” algorithm.

“As far as controlling what we can control, I think we have a decent shot of making it to regionals,” Dufresne says. “That’s been our goal this season. Last year, we were establishing ourselves as a decent team. The next big leap forward is trying to make the playoffs, and it’s definitely doable. With everybody healthy, I think we have one of the better teams in our division.”

Literally and figuratively, it has been a long, hard road. But these are hockey players. They like it that way.

“You know you have a good team when you feel everyone is like your brother and you have everyone’s back,” says junior forward Miles Manson, who grew up playing Kansas City hockey alongside Preston McConnell, a duo that now forms the high-speed line that provides much of KU’s scoring, as do Bockman, sophomore forward Dawson Engle and 21-year-old freshman defenseman Johan Steen. “We had that a little bit here and there those first couple of years. Last year it really started to become evident. This year? It’s crazy.”

Steen, who was born in Sweden and moved to Dallas when he was 3, played four years of elite “junior hockey” in Dallas, Omaha and British Columbia. When New York’s Niagara University last year offered Steen a scholarship, he realized he could not accept. He was cooked.

“I played around 250 junior hockey games, with practice every single day, plus travel,” Steen says. “I just didn’t feel like going up there to play. So I came here.”

Steen had spent two years visiting his girlfriend, KU student Faith Whiteley, on quick visits to Lawrence when his schedule allowed. He says he spent more time in Lawrence than any other college town, and it already felt like a second home.

“The University of Kansas is the place I wanted to be,” he says. “It’s the best choice I’ve made so far.”

The one thing he didn’t want was hockey. Hockey found him anyway, and, with Whiteley’s encouragement—“She’s the one who convinced me to have my gear shipped from Dallas,” he says—Steen grudgingly accepted an invitation to join a KU practice. Expectations were low.

“I was trying to have an open mind,” he says. “Just try to have some fun, go meet some of the guys. That first practice, they all came up to me and introduced themselves, started talking to me, and it just clicked. We got along from day one.”

Steen wanted no part of the daily rigors of varsity NCAA athletics. But club hockey? With a couple of practices and two games a week? That felt right.

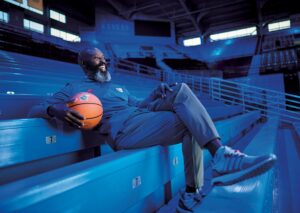

“We’re guys who love the game. We’re here for school first, but we go out there on the ice and we know we’ll battle for each other. You put on that jersey, and you’re playing for the logo on the front, not the logo on the back. You’re playing for your school. You’re representing KU.”

Time and money are the two things in shortest supply for college students. KU hockey players choose to give generously of both, and, to a man, they say their sacrifices will all be worth it if the program continues to grow and prosper.

Preston McConnell sees resurgent team pride every time he and his teammates enter their hallowed hockey locker room. Amid the swirling sea of overflowing equipment bags, skates, helmets and sticks, the KU jersey never touches the floor. It’s a matter of respect.

“The first couple years were really tough. Maybe you don’t want to put this in your article, but, truthfully, it was almost embarrassing for us to put on that jersey. We were going through such a hard time trying to get this program going. But seeing where this is now, throwing that jersey on is a very special feeling.

“Not very many people get to play a sport with the sacred Jayhawk on the front of their jersey, representing the University of Kansas. I’m going to miss it more than anything I’ve done in college. I’m going to miss playing for KU very much.”

Yo juego hockey?

You’d better believe it.

Intramurals and club sports at KU

Intramural sports offered by KU Recreation Services annually attract about 3,000 students, many of whom participate in multiple sports and all of whom compete against other KU students.

Short of varsity athletics, the highest level of competition is sport clubs, including men’s ice hockey. Most of the 30-plus teams, with about 1,200 athletes, compete against other schools.

Club teams are funded with a campuswide fee of $4 per student per semester. At its current allocation of $9,000, ice hockey is among the best-funded teams, although club officers hope financing grows as the club continues its resurgence.

KU’s sport club teams have access to a dedicated weight room (to avoid overcrowding in the public areas of Ambler Recreation Fitness Center), trainers at games and assistance with travel logistics, but the clubs are student-run—which Assistant Director Dave Podschun views as an important aspect of the experience.

“If you take it seriously, and if you’re successful, that’s a big thing for those who choose to take on leadership positions, especially for ice hockey,” Podschun says. “Their budget is probably upwards of $40,000. Who else, as a 20-year-old getting out of college, can say they managed a budget of $40,000?”

Despite the long hours he dedicates to team logistics on top of practices, games, and a double major in geology and chemistry, that’s a benefit not lost on club president Will Dufresne.

“I’ll definitely talk about it in interviews,” he says. “When they ask about something you solved as a team, or the time you had to battle through adversity or work through something that’s less than ideal, the examples from hockey alone can answer those questions.”

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Crimson & Blue.