In the summer of 1934, a 10-year-old girl watched as a seriously injured boy was carried into her father’s rural medical office. It was harvesttime in Kansas, time for the local boys to shoot the terrified rabbits flushed out by the advancing combines. In the dust, excitement, and confusion, one of the boys took shotgun blasts to his abdomen and thighs. The girl’s father was delivering a baby at a remote farm and could not be reached. Her mother, a nurse, did what she could to staunch the profuse bleeding and triage his wounds, but the boy had to be put in the back of a truck and driven over unpaved roads to Wichita. I thought right then, if Mother had been a doctor, we could have treated him here and not sent him off. I realized being a nurse would be inadequate. I absolutely decided right then to become a doctor and stuck to it!

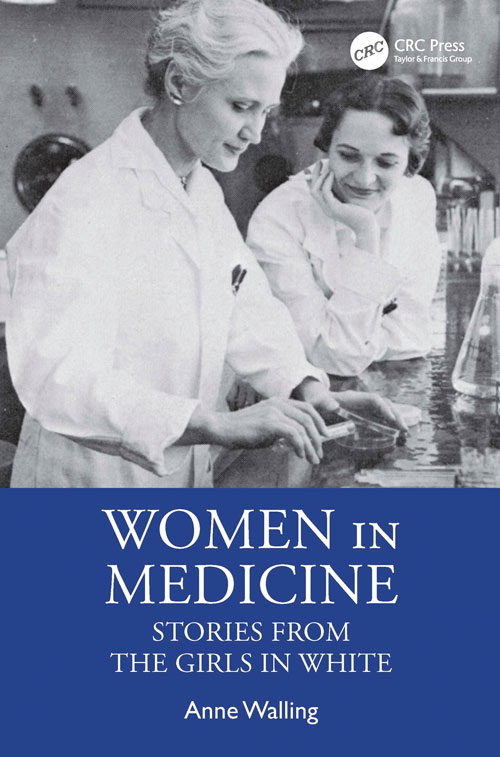

This harrowing memory of a summertime emergency in rural Kansas—and a young girl’s vow to become a doctor when women in the profession were few—helped spark a project that captures the memories of senior women physicians who are KU alumnae. Women in Medicine: Stories from the Girls in White, which will be published in July, contains anecdotes from 37 pioneering women who entered the School of Medicine during the pivotal years from just after World War II to the early 1970s. They represent 17 states, spanning all regions of the nation, and they practiced in 13 specialties, working in varied settings from rural clinics to metropolitan research institutes. The most senior physician graduated in 1948 and was 96 years old when the video interviews occurred during the winter of 2020-’21.

Dr. Anne Walling, professor emerita of medicine and a faculty member since 1981; co-investigators Kari Nilsen, associate professor, and Morgan Weiler Gillam, c’18, m’22; along with other senior faculty, staff and students, began the project in 2019, working with Jordann Parsons Snow, c’08, and the team from the KU Medical Alumni Association to connect with alumnae. (Snow now continues her work with KU Medical Center campuses as assistant vice president for University relations at KU Alumni, following the recent integration of the Medical Center’s alumni groups into the larger organization.)

The Women in Medicine study expands on a 2018 Medical Society of Sedgwick County project, “The Only Woman in the Room,” (OWR), which included memories from 23 physicians in the Wichita area. OWR revealed substantial variation between the experiences and attitudes of women who forged their way to medical careers in the middle of the 20th century and those who began after 1975, the first year when women represented about 25% of KU’s first-year medical students. “Although they were still a minority,” Walling writes, “once women represented one quarter of the class, they were no longer so unusual, isolated or invisible.”

Thankfully, progress has continued. By fall 2023, 43% of first-year KU medical students were women, and in fall 2024, women represented 60% of the first-year class, including the campuses in Kansas City, Wichita and Salina.

Women in Medicine focuses on a larger sample of women who entered medical school in earlier years, and it counters presumptions that pervasive misogyny and mistreatment clouded overall careers. Only one of the participants remained bitter about her training, and nearly all expressed professional and personal fulfillment despite early struggles. They appreciated the opportunity to share their stories with a wider audience; as one doctor put it, “We need to write our own history before someone writes it for us!”

If the reference to “Girls in White” seems off-putting for a book that hails the resilience and strength of women, the juxtaposition slyly packs purpose: Walling explains that the phrase is a subtle retort to a widely known 1961 book, Boys in White, which chronicled the experiences of men studying at KU’s School of Medicine in a bygone era. The modern rendition, Walling writes, “gives voice to the women who were excluded from that study as being irrelevant to the ‘man’s work’ of medicine!”

The following excerpt is adapted from Chapter 10 of Women in Medicine, “Medical School: Into the Man’s World.” Comments from the alumnae appear as they do in the book: in italics, without attribution.

—The Editors

First impressions

I started in 1970—scary. I was terrified but wanted to do well.

Our interviewees vividly recalled their first days at the Medical Center (KUMC). They described a gamut of emotions. Excitement and eager anticipation alternated with anxiety, fear of failure, and concerns about loneliness and social isolation. Everyone was determined to succeed but worried about the academic and other challenges ahead. They had all heard about the brutal pace and volume of learning in medical school. Although they had done well in college, they worried how they would fare in a class of competitive high achievers. Those who did not have particularly strong backgrounds in science were especially concerned.

Most of the class had been science majors. One friend had a master’s in microbiology, another a master’s in comparative anatomy from Cornell University. Most of the students were Phi Beta Kappa. I felt slightly behind in science initially but worked hard and did well.

Really struggled and worked hard to get in. In college, you are used to being in the top 10%, but things were different in medical school—everybody had been at the top of their class.

In addition to academic concerns, our interviewees recalled being anxious about personal and social issues. They were curious about their classmates and hoped they would find friends and fit in with other students. Those who were shy quickly realized that medical school required a robust attitude.

I was excited, scared, and nerdy, always had my nose in a book. I was so timid and shy but found out being shy doesn’t work in medical school!

Despite years of preparation and anticipation, several remembered feeling scared and overwhelmed in their first days at the Medical Center. This was particularly the case for women who had attended small colleges, especially if they also came from small towns or rural areas.

After senior classes of 15-20 in college, the class size was daunting.

I was incredibly naïve. I felt like I came from a little town and a little college and would be right in the middle of the class—and I was.

Incoming medical students who had attended KU in Lawrence knew several classmates and others on the Kansas City campus. Students who were not KU graduates felt at a disadvantage.

Many of my classmates knew one another from KU undergraduate or other colleges. I only knew a few of the men who had gone to Rockhurst High School.

It felt hostile, hot, uncomfortable, not welcoming, especially for non-KU grads. KU grads all knew one another.

The 1970s saw the admission of large numbers of young women who resisted being stereotyped and could pose a threat to long-established practices and assumptions. Against the turbulent background of that time, any student requests for change were likely to be perceived as instigated by radicals and troublemakers (including disruptive feminists); hence, any calls from women for accommodations or complaints about mistreatment were likely to meet with suspicion and/or resistance from institutions unwilling to show any signs of weakness. All students from minority groups were expected to be deeply grateful for admission and not presume to ask for any further concessions from the institution or colleagues.

Our interviewees were certainly not troublemakers, but they struggled to succeed in an environment designed for and governed by men. As in the majority of U.S. medical schools of that time, masculine beliefs, attitudes, and perspectives determined and maintained the institutional culture of the KU School of Medicine. They permeated all aspects of the lives of students, from politics and policies to practical details of daily operations. Conflicts and intransigence over accommodations for women could arise over any issue, even personal matters, such as clothing.

Practical issues: What should I wear? Where can I change? Where do I hang my purse?

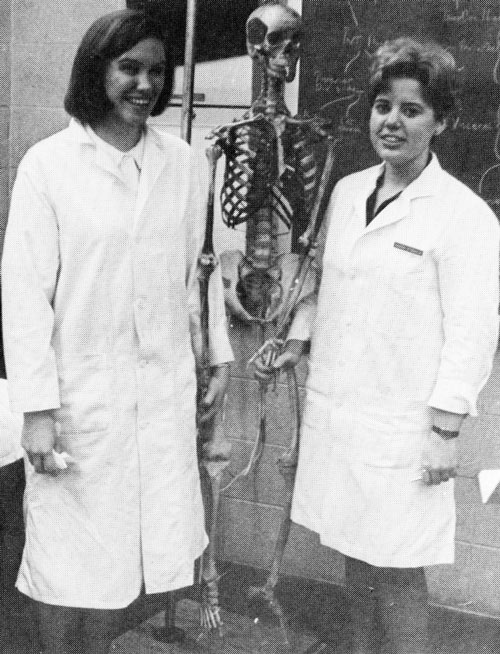

Medical students were expected to always dress appropriately and required to wear a uniform in clinical situations. For third- and fourth-year students, the uniform was worn at almost all times, including at night calls. The required short white jacket and trousers were adapted for female students by the substitution of a straight white skirt (not too short) and hose. Uniforms for male students could be purchased in the student bookstore, but women had to find their own.

Skirts were often impractical, as students were kept busy with ward tasks and were physically active. Examining and manipulating patients, performing tests and treatments, resuscitating patients, delivering babies, and multiple other activities required greater freedom of movement than could be easily and modestly achieved in a knee-length straight skirt. The attention to women wearing short skirts at all times was perceived by our interviewees as impractical, inappropriate and creepy on the part of lewd-minded male faculty members and others.

Women always had to wear skirts. The rules were especially enforced on OB-GYN rotations. Ridiculous, as you were always clambering over things or bending down, and unless you wore ridiculously long skirts, it was embarrassing.

For surgery, we had to wear surgical dresses. On one occasion, I couldn’t find a small surgical dress, so I put on a large one. The professor stopped the surgery, called me out for being “dressed inappropriately,” and sent me out to find a smaller dress. This same professor insisted female students wore dresses or skirts.

One redoubtable mother came up with a solution and browbeat the dean into accepting it:

Women were not allowed to wear pants, had to be skirts. My mother went to Dean [David] Waxman. Complained about her daughter having to climb on beds or resuscitate people with other able people being able to look up her skirt! She told him this is how it is going to be—she will wear culottes, and so will the other women. He said, “Okay, but they still can’t wear pants.” She made culottes for all seven women in the class.

Clothing issues for female medical students were most problematic in the departments of surgery and obstetrics and gynecology. These departments were the strictest about enforcing the uniform code for routine clinical work and had stringent rules about attire in the operating rooms. Male students had access to a plentiful supply of surgical scrubs and use of the physicians’ changing facilities and lounges. Female students were required to wear surgical scrub dresses—never pants—and nursing supervisors could be obstructive in providing dresses and allowing use of the nurses’ changing areas.

Women in the first groups of students to transfer to Wichita encountered great hostility from the senior surgical nurse supervisor at one of the hospitals. One student was told to buy her own surgical scrubs. She complained to the hospital administrator, citing illegal discrimination and hinting about legal action. The supervisor then issued her with two surgical dresses so tight they fit all my curves, but I wore them anyway. Never looked so sexy. Early female students at another Wichita hospital described changing in a public restroom after being barred from both the physicians’ and nurses’ changing areas. The intervention of a senior surgeon was necessary to allow female students to use the nurses’ changing facilities. Even then, students were not welcomed and encountered difficulties in securing surgical dresses, hair coverage and other necessary equipment.

Where can I sleep?

During the third and fourth years, students were regularly required to remain in the hospitals overnight for admissions or to respond to inpatient needs. The students and interns needed places to sleep between calls. The most typical arrangement was a small room (often a converted patient room) adjacent to the patient care areas, operating rooms, or delivery suites. Accommodation was basic, consisting of two or four bunk beds, a desk and chair, and a telephone. Most rooms had an adjacent small bathroom with a shower.

In the 1940s and 1950s, our earliest interviewees reported being required to sleep in the nurses’ dorm and recalled being locked out when trying to return from the wards in the early hours of the morning.

The housemother was NOT pleased to be woken up, especially if this happened several times during an obstetric case, when I had to check frequently on a woman in labor all night.

Individuals came up with their own arrangements. Over time, the regulation was increasingly ignored, and the women shared accommodation with their male classmates and interns.

When on call, female students were supposed to sleep in nurses’ dorm—a long way from the wards—but they mostly slept in bunks in the call room, where the male students slept. Awkward, but never any problems.

All participants from the 1960s onward recounted sharing overnight accommodation with male colleagues. Some commented that they mostly slept in surgical scrubs to save time and avoid issues over changing in mixed company. They recalled few problems, apart from some embarrassment or teasing, and saw the sharing as part of the expectations of proving they had the right attitude to be medical students. Some perceived that the guys were more embarrassed than we were. Apparently, some of the male students’ wives were not pleased with the arrangements.

It was just the way it was

Sexism and casual misogyny were pervasive in U.S. society during the decades covered by our interviews. As traditionally male enclaves, medical schools may have been more overtly sexist than other environments, but they were by no means unique. Interviewees who had careers prior to medical school reported that the atmosphere was better for women in medicine than in other professions or in business.

I was a secretary after college. The only way you were going to work your way up was on your back.

I think things were better for women than in other fields, like business.

Attitudes and behaviors that are now considered unacceptable or even repulsive were then accepted as normal and often tacitly encouraged by faculty and others. Even the female students did not regard the sexism as abnormal for that time.

There was a lot of sexually inappropriate behavior that I really only recognize retrospectively.

The class yearbooks convey an immature “frat house” image with frequent sexist or lewd comments and illustrations, especially of nurses in provocative poses. The 1969 Yearbook even had a Playboy theme with a highly sexualized cartoon of a scantily clad female student on the cover.

Comparisons and reflections

Our participants vividly recalled their first impressions of medical school and their attempts to adjust to the unique environment they had worked so hard to enter. Although they knew classes would be large and male-dominated, the reality came as a shock, especially for those who had enjoyed small, student-centered classes with good representation of women during their final years at college. The institutional size, masculine culture, and uncompromising regimentation were daunting. The incoming female students knew they would be members of a minority that was not necessarily welcomed, could be resented, and was vulnerable to unfair treatment. They recognized that their colleagues, faculty, staff, and administrators held mixed and probably negative views on women in medicine.

Nevertheless, our interviewees conveyed a theme of being prepared for challenges and difficulties with comments like, I knew what I was getting into, or, I was determined to show I could succeed. They epitomized the priority characteristic for female students described in a 1976 review:

“Until recently, toughness of character has been the first prerequisite.”

Our interviewees indicated several reasons for the lack of organized action by the female medical students. Most commented that they did not have the time or energy to organize like-minded classmates, analyze issues, strategize about solutions, and attempt to negotiate with an unsympathetic but powerful administration—and they doubted such negotiations would be tolerated, let alone be successful. They stressed that a woman had to be resourceful, independent, and self-sufficient to prove herself in medicine, and solving her own problems was one way to demonstrate these qualities—and prove she would not be a drag on her colleagues by expecting special treatment or having too many needs. This resonates with a 1967 survey of female medical students who were unsympathetic to special accommodations for women, citing “the stringent process of natural selection is necessary to ensure that those girls who reach medical school are prepared to give what the training demands.”

Similarly, the KU women were very aware that any request for special accommodations bolstered suspicions about their commitment to medicine and willingness to make sacrifices for the profession.

The whole atmosphere was “married to medicine.” You’re not a good doctor if medicine doesn’t always come first.

In the 1960s and the 1970s, medical schools were intolerant of student activism of any type, and there was little sympathy for student “rights.” For students and others without power, the risks of speaking out or having the reputation of a troublemaker were high. An outspoken woman was likely to be stigmatized as a “radical feminist,” with real negative consequences, such as being dismissed or prejudicing letters of recommendation for internship or residency positions. In addition, individuals could not be certain of support from fellow students, as all were calculating the potential damage to their academic survival and professional prospects from any negativity in their records. Both the KU women and national surveys in the 1960s and the 1970s show that female medical students distrusted their female colleagues to support moves to address sexism and improve the environment.

All medical students, especially women, were very aware of the risks associated with causing trouble or being perceived as too pushy. In this environment, it is understandable that women generally tried to solve issues on their own or kept my blinders on and ignored things, kept marching forward.

They needed all their ingenuity, adaptability, resilience, intelligence, and humor to navigate the large cast of characters and multiple experiences of medical school.

By Anne Walling

$55.99 paperback, $230 hardcover

CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group