Bill Self wasn’t diagramming a defense when the Oklahoma City Thunder—reigning NBA champions on pace for a record-setting title defense—came up. He was talking about something harder to draw.

Asked recently whether highlighting the Thunder’s rugged, relentless defense would inspire buy-in when coaching college players, Self responded, “It’s a great question,” then pivoted away from schemes and statistics. What Self values in Oklahoma City, he said, isn’t just elite play on both ends of the floor. It’s a culture built on shared credit, collective accountability and visible joy.

“That is the culture that I would be talking about, more so than Xs and Os,” Self said, “because if you have that culture, then naturally the other stuff will come a lot easier.”

For a Kansas team still sharpening its identity, the timing of that reflection—and Self’s disclosure that he recently texted his thanks to Thunder GM Sam Presti for a remarkable run that “has been good for our sport and our game”—is notable.

With Big 12 play getting underway Jan. 3 at Central Florida, the 10-3 Jayhawks enter the heart of the season with a strong defensive foundation and an offense that remains uneven. They have defended at a high level, limited clean looks and protected the rim consistently; at the same time, Self has been frank about offensive stagnation—slow pace, sticky possessions and too much standing.

Kansas, he has said, is not yet an execution team. That reality places a premium on movement, trust and role acceptance—the very qualities Self admires in Oklahoma City.

The Thunder have become historically dominant defensively, forcing turnovers, shrinking space and suffocating opponents possession by possession. But Self’s fascination runs deeper than efficiency ratings. He sees a group that genuinely functions as one unit. Stars don’t stand alone. Interviews are shared. Endorsement opportunities include teammates. When reserves thrive, the all-stars cheer loudest of all.

“Those are the things, to me, that add to culture as much as anything, so that’s what is special,” Self observed. “Now, are they good defensively? Yes. Are they good offensively? Yes. Do they share the ball? Yes. Do they play where they like each other? Yes. There’s a lot of yesses, but it all comes down to the youthful exuberance they seem to have playing with each other as much as anything, and you can’t tell me that doesn’t bring team unity.”

Kansas has offered glimpses of that same connective tissue.

Defensively, the Jayhawks already resemble a team aligned with Self’s values. Their first-shot defense, powered by blossoming star Flory Bidunga, a sophomore forward, has been “well above average,” in Self’s estimation, and their collective effort has traveled game to game, even amid lineup disruptions. That shared defensive purpose has allowed Kansas to win without everything clicking.

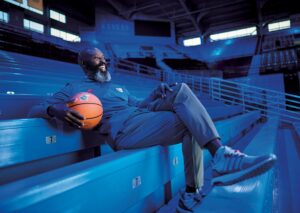

What remains is extending that connectivity into the offense. If there is an embodiment of Self’s exuberant ideal, it’s guard Melvin Council Jr., an unheralded senior transfer from St. Bonaventure whose emergence has reshaped Kansas’ backcourt.

Council’s 36-point performance Dec. 13 at North Carolina State—featuring nine three-pointers, seven rebounds, four assists and no turnovers in 43 minutes—was extraordinary, not just for its volume, but for its feel. He didn’t dominate the ball early. He responded to what the defense offered. When attention shifted, he moved it, leading to what Self considers the best road performance he’s coached in 23 seasons at Kansas.

Relive Melvin Council Jr.’s big night at NC State.

Council leads the Jayhawks in assists (his 67 are more than double Tre White’s 30 and account for 33% of the team total), ranks among the nation’s leaders in assist-to-turnover ratio, and has become a steady emotional presence. His production lifts the group rather than separating him from it—a subtle but crucial distinction for a team still defining roles.

Kansas does not resemble a roster built for isolation basketball. Especially when forced to play without superstar freshman Darryn Peterson, who missed nine nonconference games to injury, Self said his Jayhawks must function as movers, shooters or immediate passers. Standing still breaks the chain. Movement sustains it.

“We moved the ball the best this year against Tennessee (Nov. 26, an 81-76 victory), a really good team that could really guard,” Self said. “We haven’t done that, in my opinion, since then, so we’ve got to address that. Don’t take that as me being negative, but we, the staff, have got to do a better job of getting our guys to understand what works with us.”

That, ultimately, is why Oklahoma City resonates with Self.

Not as a system to copy, but as proof that when players trust one another, share the spotlight and take collective ownership—and take heed when taught that defense wins championships—everything else becomes easier. That’s the Thunder parallel Self is chasing. Oklahoma City’s stars don’t dominate oxygen. They circulate it. And in doing so, they create a feedback loop: Effort fuels trust; trust fuels freedom; freedom fuels excellence.

Kansas isn’t there yet. Self has been clear about that. But the Jayhawks are positioned to move in that direction—especially as the urgency of Big 12 competition strips away pretense. Conference games don’t reward individual agendas. They expose them.

If Kansas is to grow into the team Self envisions—one that defends ferociously, moves the ball instinctively and takes collective ownership of results—the transformation will be cultural before it is technical. That’s why the Thunder matter here. Not as a template to copy, but as a reminder: Teams that genuinely like each other trust each other, and those that share the spotlight tend to endure.

Kansas will find out quickly whether it’s ready to do the same.

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Crimson & Blue.