Bill Self knew the question would sound unusual.

“I’ve got something kind of off the wall, and I want you to think about it,” Self told Jacque Vaughn over the phone. He had just lost longtime assistant coach Norm Roberts to a well-deserved retirement, after 14 seasons at Kansas and 37 years in coaching, opening a space on Self’s bench, and now he was pursuing an idea that, in the hope of keeping it out of the social media rumor mill, Self had yet to share with anyone.

“Norm has been the most loyal guy, we’ve been together forever, but he saw this as a great time to step aside, and when that occurs, there’s obviously a door that opens and opportunity presents itself,” Self said at the June 3 news conference introducing Vaughn as the newest member of the men’s basketball coaching staff. “I could be wrong, but I think Jacque was a little surprised that I was calling. He said, ‘I’m going to take it to Laura. I’m interested enough for this conversation to continue, and I’ll let you know in a couple of days exactly what I’m thinking.’”

Turning to his newest assistant coach, Self added, “Would that be a fair assessment?”

“That’s it, Coach, yeah,” Vaughn replied, grinning.

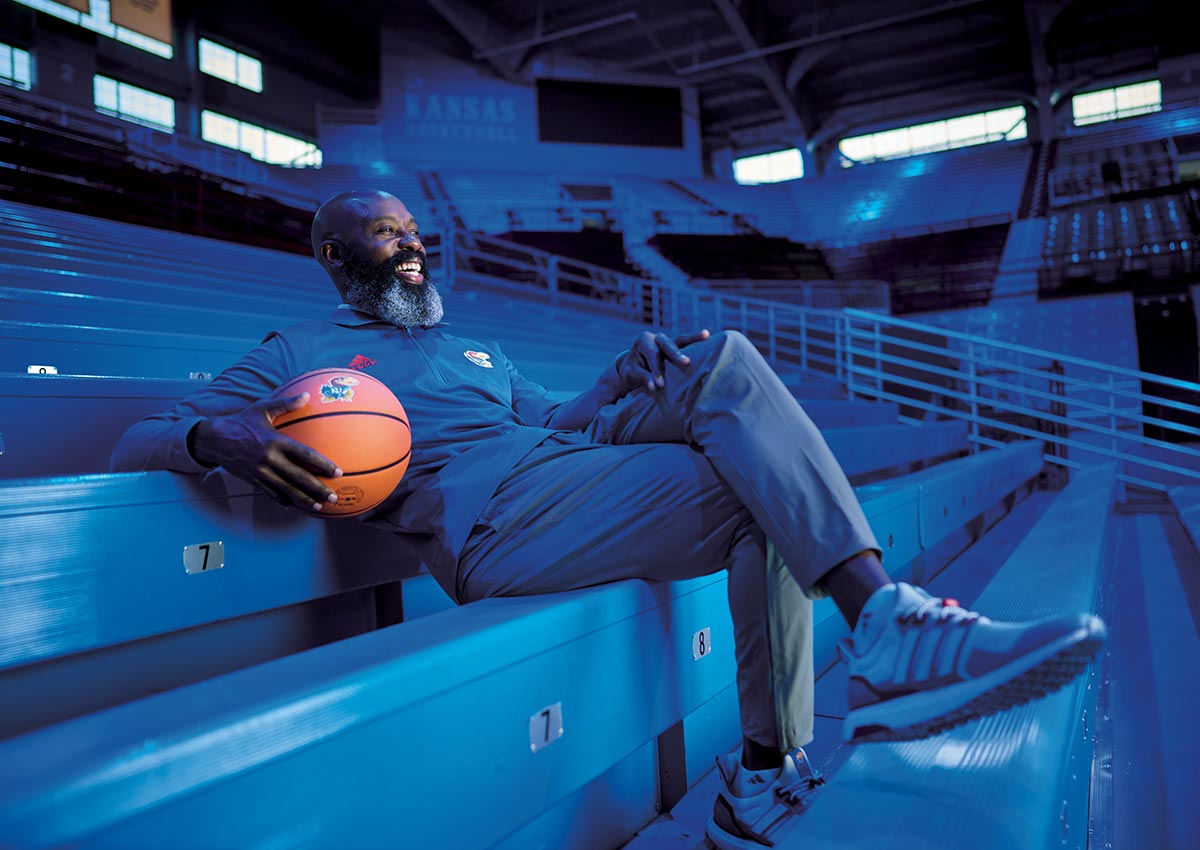

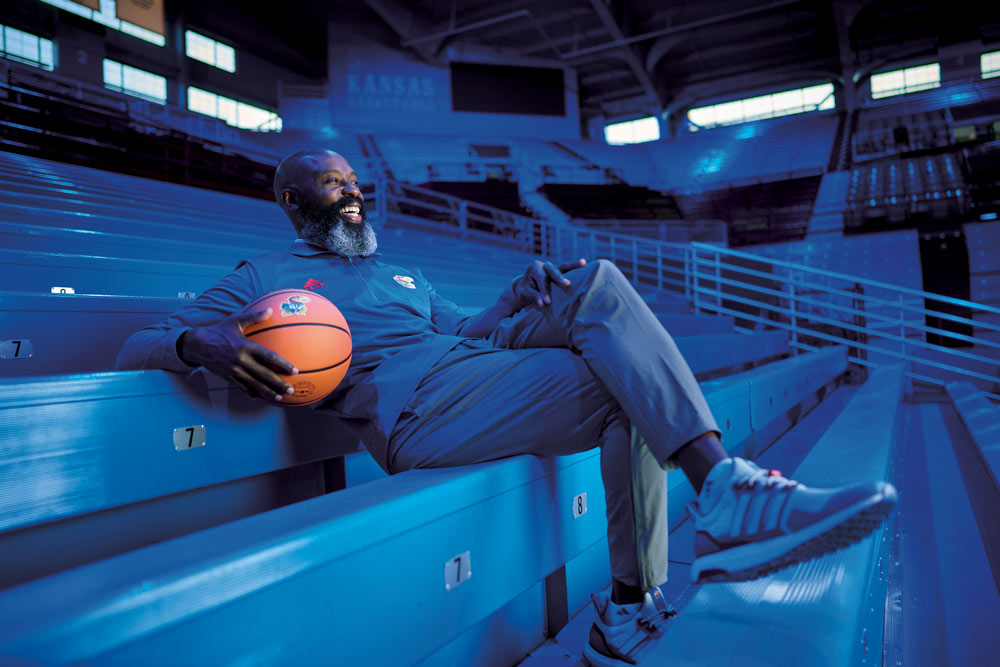

After a decade with the Brooklyn Nets, Vaughn, b’97, one of the most beloved players in Kansas history, had been living quietly in Paradise Valley, Arizona, spending his days on the golf course, evenings on dinner dates with his wife, Laura DePaolis Vaughn, c’99, and relishing family weekends at the University of Miami with their two sons. He had been an NBA head coach and spent 12 years as a player, and Vaughn had no plans to jump back into the game—at any level.

“I told my agent, ‘I’m just going to let time reveal itself. What happens, happens,’” Vaughn told Crimson & Blue in an interview in his still-spartan office within team headquarters in Wagnon Student-Athlete Center. “That’s kind of how my brain works. I always believe you are where your feet are, and I’ve tried to explain that to our kids when we moved a lot. San Antonio, Orlando, New Jersey, Brooklyn, Atlanta … we’re not going to look beyond where our feet are, so we’re going to enjoy and soak it in and enjoy these memories. We’ve always taken that approach, which I think has been beneficial.”

With the unexpected option to, as Vaughn says, return home, the family huddled. As promised, Vaughn returned Self’s call in a matter of days.

“We’re good,” he told Self. “Tell me more.”

And with that, Kansas basketball gained not just a familiar face but a unique resource: the first former NBA head coach ever to serve as a KU assistant.

“This is exciting for Kansas,” Self said, “but I don’t think you hire somebody because people like him. I think you hire only because he complements what your talents are, and he brings something to us that’s different than what we’ve ever had before. We now have a college assistant coach who was a three-time NBA head coach, who trained Kevin (Durant) and Kyrie (Irving) and all the different guys, and that brings immediate credibility to guys who want to be pros, knowing they’re going to work with somebody who knows firsthand what it’s supposed to look like.”

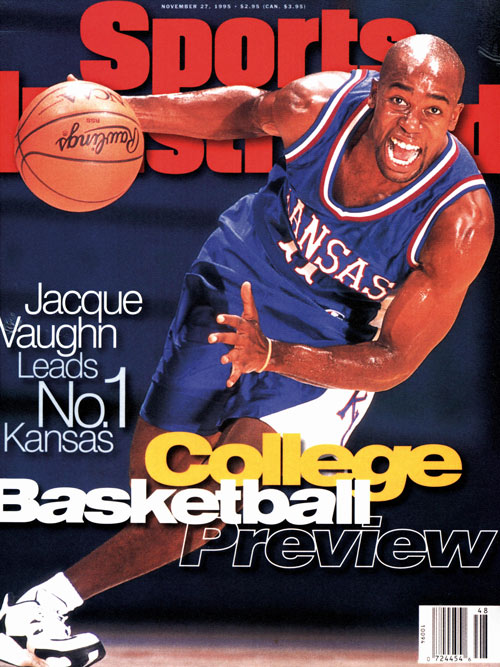

Indeed, Vaughn represents a rare blend of history and expertise. He remains third on KU’s career assists chart with 804, and his No. 11 jersey hangs in the Allen Fieldhouse rafters. He was the 1996 Big 8 Player of the Year and the 1997 Academic All-American of the Year. After a 776-game NBA playing career that included a championship with the San Antonio Spurs, he shifted seamlessly into coaching, spending two seasons as an assistant under Gregg Popovich in San Antonio before leading the Orlando Magic and twice guiding the Brooklyn Nets.

For a program that thrives on developing NBA talent, Vaughn’s presence is a selling point.

“The great thing is, when I accepted the job, I had probably 20, 25 calls from assistant GMs, GMs, personnel directors across the league, so the direct feedback for our guys will, I think, be beneficial,” Vaughn says. “And then I had the luxury of coaching guys who are top 75 all-time in the NBA, and hopefully I can use that experience to help our guys.”

Yet Vaughn resists reducing his value to résumés or networks. “Players are players,” he says. “The talent level could be different, but you still listen with intent, you’re truthful, you still pull for them and want them to get better. That doesn’t change.”

Vaughn has worked with all-stars and rookies alike, and prides himself on coaching bigs and guards. He points to Nic Claxton, whom he mentored in Brooklyn into a $100 million player, as an example of development done right.

“A lot of the guys who will come to the University of Kansas want to play in the NBA, want to have a life that is associated with basketball in some way, and the last 25-plus years of my life, I’ve walked those same steps, come across some of the questions they’ll have to answer, whether it’s from parents, siblings, friends, agents, management, coaches. I’ve lived that life.

“Deep waters, and sometimes those waters can be treacherous. I have no ulterior motives but to help them.”

Vaughn credits the good fortune of being drafted by the Utah Jazz, where Hall of Fame coach Jerry Sloan led a perennial contender that featured the likes of John Stockton, Karl Malone, Antoine Carr and even Vaughn’s former KU teammate Greg Ostertag, ’95.

“Those guys, they were men, who had kids and who had been paying bills for a long time,” Vaughn says. “Without that veteran leadership, I’m not sure how long I stay in the league. I played for 12 years, and I give a lot of credit to being drafted by Utah and being around a group of veterans who taught me how to prepare myself as a professional every single day.”

Now Vaughn intends to do the same for the young men wearing his beloved Kansas jersey, and his message packs power in its clarity: “I like to do simple better. There are no shortcuts. I believe in putting in the work, and the results will come from that work.”

Along with his enthusiasm to rejoin the KU basketball family and learn college coaching under Self—“The opportunity to be around a Hall of Famer who has two national championships and is taking our program to a different level really guided my pivot to come back home”—the move to Lawrence is even more rewarding for its impact on the one thing that matters more than basketball: family.

“When you think about it, all the stops we had, the four of us, we always had to get to know the community, how to travel, where to go to eat, where to live,” Vaughn says. “We didn’t have to do that here. We just got reacquainted here. We’ve walked these same streets before.”

The memories flood back: the Los Angeles kid experiencing his first Kansas winter (“Are you kidding me? I thought I had a winter jacket. I’ll never forget that”), walking the Hill to class and down the Hill to graduation, his four years living with Scot Pollard, d’97, in suite 412C of Jayhawker Towers.

“I tell people, once you come here, you feel it’s different than any other university. It’s different than any other quote-unquote college town. And for a kid coming from California to say, ‘I’m here in Lawrence, Kansas, and I love it,’ that means something to me, and it always has.”

That perspective will shape Kansas basketball as much as his NBA experience. Vaughn knows today’s players face pressures he didn’t—social media, NIL contracts, even taxes, which he recently helped one of his players navigate. But he also knows the fundamentals haven’t changed: preparation, honesty, teamwork.

“The enthusiasm is back,” he says. “I woke up at 4:30 a.m. the other day, like it was training camp. That’s a good sign.”

For Kansas fans, Vaughn’s return reinforces continuity. His jersey hanging high above Naismith Court is a reminder of his playing days, and his new sideline perch next to Self symbolizes the program’s reach—from Allen Fieldhouse to the NBA and back again.

“We are very, very proud and excited about Jacque coming in,” Self said, “and making us better.”

Three decades after his first days on campus, Jacque Vaughn is home again, ready to help lead the program he once helped define.

“Me coming back, coaching a group that’s playing on the same floor I played on, being able to talk with guys about what my path has been, hopefully guiding them and being a mentor and a coach and someone who is pulling for them more than they’re pulling for themselves … yeah, I think that’s pretty cool.”

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Crimson & Blue.